An encouraging story of how God is moving in Albania.

When Asim Hamza was growing up in communist Albania in the 1980s, it was the third poorest country in the world. The farm technology hadn’t been updated since the 1920s. Lines for milk stretched 80 people long before dawn. Pharmacies carried nothing but aspirin. Electricity didn’t reliably turn or stay on. Religion was outlawed—making the sign of the cross could land you in jail for three years, owning a Bible was five years.

Hamza had no idea anything was wrong.

The government-controlled television, during the two or three hours it was on each day, showed images of children starving in sub-Saharan Africa. “We were told that was happening everywhere,” Hamza said. “They said, ‘You are the happiest kids in the world.’ And we believed it. We were so thankful to the Communist party leader.”

Back then, “Albania was one of the three most closed countries in the world, along with North Korea and Mongolia,” Campus Crusade for Christ missionary Don Mansfield said. He became Cru’s country director for Albania in 1991, when the communist government began to topple. He’d never been there before.

“I remember I was in a meeting in Holland with all the global missions agencies,” Mansfield said. “At the time, I didn’t know anything. They were talking about what was going on, and I raised my hand. I asked, ‘How many believers are there in the country?’”

He was expecting a guesstimate, or maybe a percentage of the population.

“Do you know Sonila?” one person asked.

“Kristi?” suggested someone else.

“Maria is a Christian.”

“People were throwing out names, and I got to 16,” Mansfield said. “Everybody looked around and went, ‘Does anybody else know anyone else?’”

No one did. But today, Mansfield could name hundreds. The Joshua Project estimates there are 17,000 evangelical believers in the country. While half of that growth came in the first decade the country was open, the evangelical growth rate is still nearly twice the rate of the rest of the world (4.6 percent compared to 2.6 percent).

“It’s been a remarkable story of seeing what God has done in one lifetime,” said The Orchard Evangelical Free Church senior pastor and TGC Council member Colin Smith, who spoke at the region’s first TGC conference in 2019. “It’s an amazing change.”

To be sure, “we’re still small, and we’re not significant in the eyes of this world,” Light Church Tirana lead elder and TGC Albanian Council member Andi Dina said. “But we have a big God, and we worship him. We know he’ll build his church, and the gates of hell won’t prevail against it.”

World’s First Atheist State

Even before supreme ruler Enver Hoxha declared Albania the world’s first atheist state in 1967, evangelicals were few and far between. The population was primarily Muslim (70 percent, a heritage from the Ottoman Turks), followed by Greek Orthodox (20 percent, primarily along the border with Greece) and Roman Catholic (10 percent, mostly along the sea that separates Albania from Italy).

The evangelical Christians—by one count there were about 100—were largely gathered around a Baptist mission in the city of Korce. But the week after Pearl Harbor, the government kicked all American missionaries out. (Italy, a member of the Axis, was then occupying Albania.)

Foreign missionaries wouldn’t be allowed back for another 50 years. Hoxha, who came to power after World War II, didn’t just believe religion was opium for the masses. He also saw it as an issue of state security—Roman Catholicism meant influence from Italy, Orthodoxy came straight from Greece and Serbia, and Islam meant interference from Turkey. To allow Protestants would mean meddling from the West. Not only was practicing religion illegal, then, but so was believing it.

Hoxha’s enforcers started by burning four Franciscan priests to death, then turned mosques and churches into factories (minarets became chimneys) and shot an elderly Catholic priest for baptizing children. Hundreds of clergy were tortured and imprisoned for decades, forced to do hard labor in mines and sewage canals. Government-produced films that accused clerics of corruption, corroborating with foreign powers, and arranging forced marriages were broadcast over and over on the television channel. Newspapers mocked religious leaders on trial for being traitors.

Eventually, Albania’s borders were sealed so tightly—against both the democratic West and the communist Soviet Union and China—that nobody could get in to see what was going on, much less evangelize.

But that didn’t keep the Bibles out.

By Air and Sea

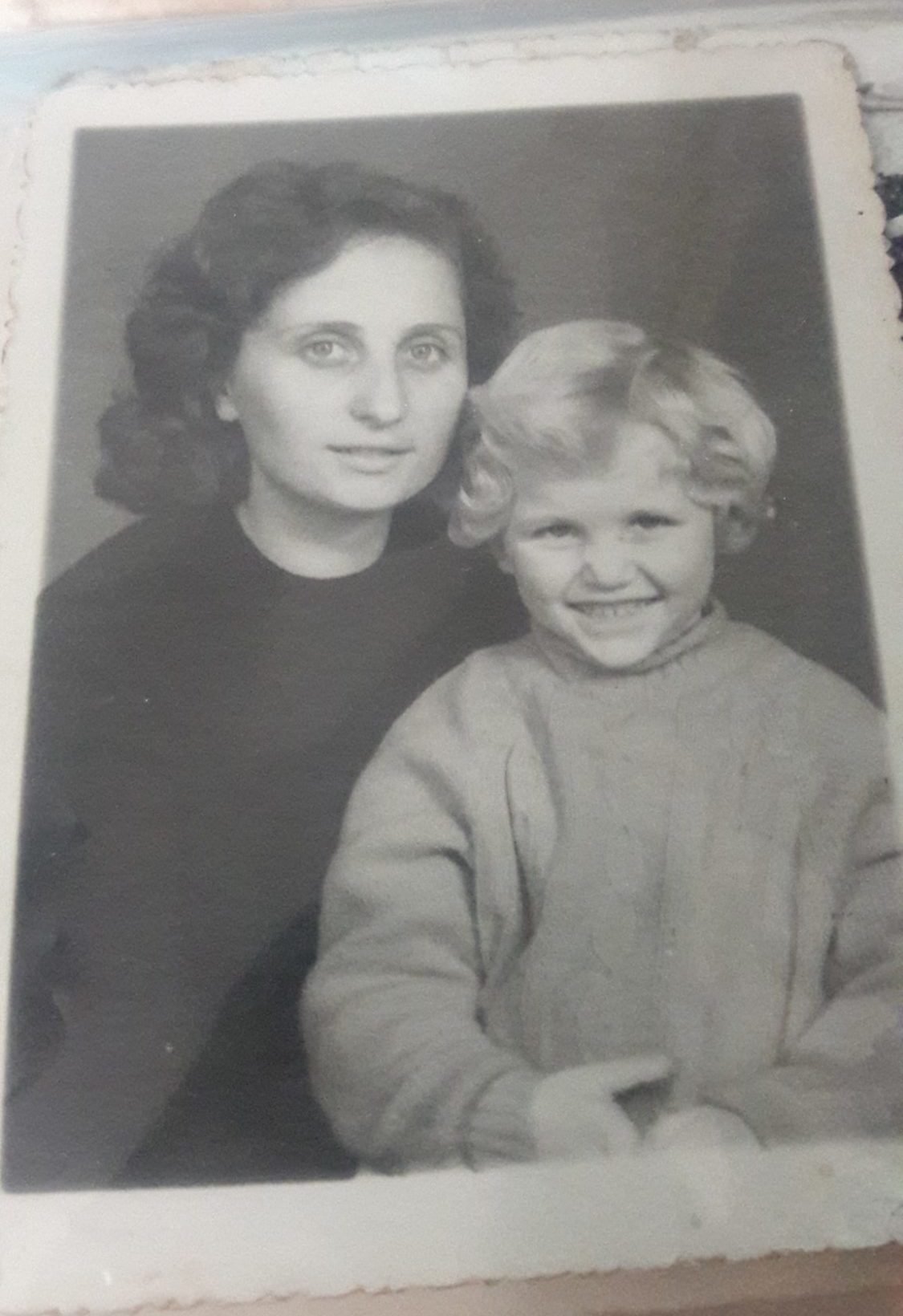

Albert Kona grew up in the town of Durrës, on the Adriatic Sea. In his childhood photos, you can count his ribs. He remembers his parents getting up at 2:00 a.m. to stand in line for bread or milk.

His family had been Eastern Orthodox, though he didn’t know that. One day, when playing in an antique wooden trunk of his grandmother’s, he found part of an old book with some pages ripped out. In it, he read about Peter and John.

He wasn’t the only one to get his hands on Bible stories. After World War II, some American GIs flew over Albania and tossed out Bibles attached to parachutes. Most of them were gathered up by the government, but one man found about 12 chapters from the Gospel of Luke. “He understood who Jesus was and what Jesus had done,” said Kona, who met the man years later, after the country opened up. “He had a true and simple faith.”

In 1985, an Operation Mobilization (OM) ship anchored 12 miles off the Albanian coast, just far enough out to be in international water. Those on board dropped copies of the Gospel of Mark, freshly translated into Albanian, into gallon-sized ziplock bags. They blew each bag up with air so it would float. Then when the tide was just right, they plopped the Bibles into the water, praying they’d wash up on shore. In Kosovo, OM staff were standing on the banks of rivers that flow into Albania, doing the same thing.

“That was about all you could do,” Mansfield said. Some Swiss Christians had tried to smuggle Bibles in on a rare visit, but when they got to the airport, all the Bibles they’d surreptitiously given out were returned to them. “You forgot these,” the government officials said.

Even after Hoxha died in 1985, the country remained locked down. It was another six years before the borders finally opened. It had been five decades, and nobody knew what to expect. Mansfield remembers walking to the beach on his first visit, the people moving away from him.

Then three young men swaggered toward him, unafraid, asking questions. “Where do you come from?” “What do you do?”

“I have the most amazing job on the planet,” he told them. “I get to tell people how they can know Jesus Christ.”

The leader, Leonard, turned to look at his friends. “Wasn’t it five minutes ago, we were talking, and we said, ‘We have got to find someone to tell us about Jesus’?” he asked them, astonished. Then, turning to Mansfield, he offered the easiest evangelistic opening there is: “Will you tell me about Jesus?”

Stunned, Mansfield shared the gospel with the young men. Only later did he wonder how Leonard even knew to ask about Jesus. When he asked, Leonard said he used to work for the coast guard. One day while on the beach, he’d found a ziplock bag with a Gospel of Mark tucked inside.

“God will have his way,” said Mansfield, who still tears up over the story. “When God wants to move, he’s going to move.”